A heads-up, for those who might be interested.

In under twelve hours time the Juno mission to Jupiter will decelerate, to enter orbit around Jupiter.

It is the fasted man made object yet created, travelling at 160,000 mph.

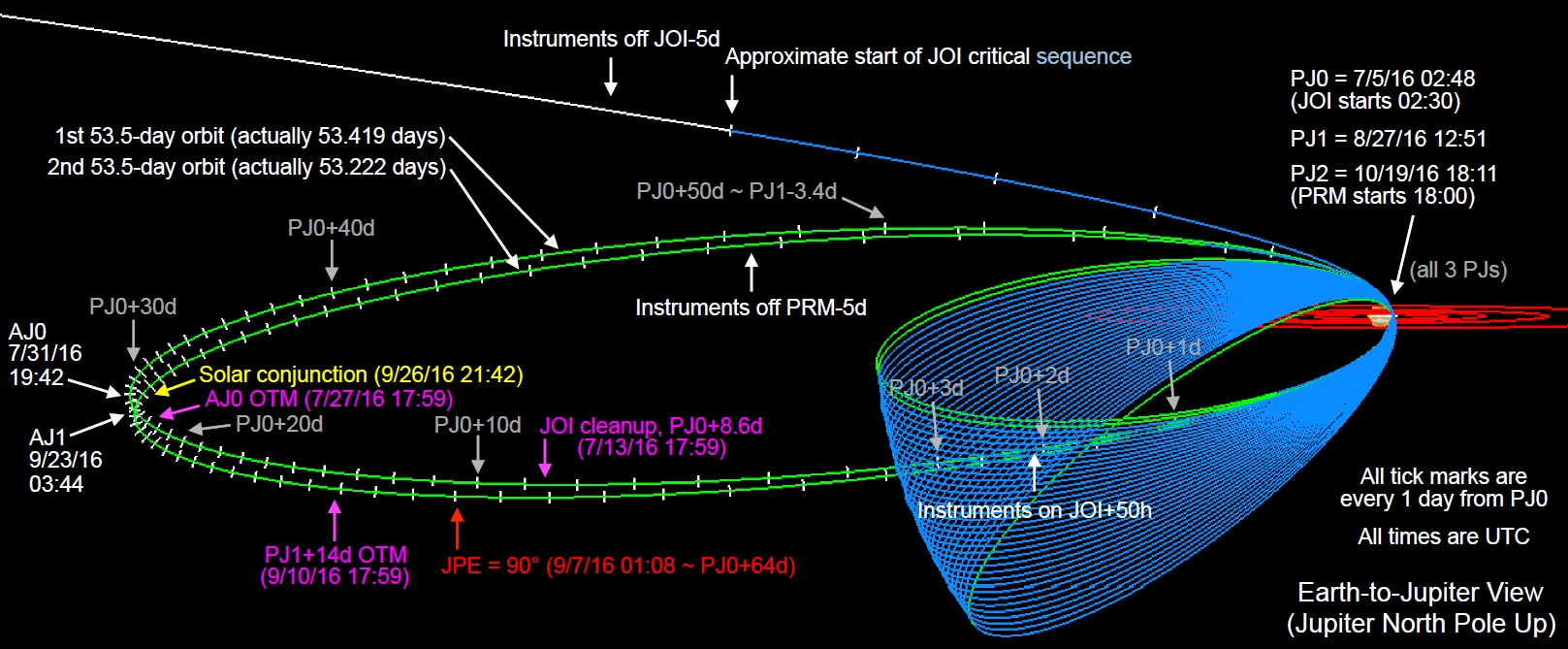

At about 03:15 AM GMT tomorrow, 5 July (still 4 July in the USA ![]() ), it’s engine will fire, to decelerate it until it can be captured by Jupiter’s gravity.

), it’s engine will fire, to decelerate it until it can be captured by Jupiter’s gravity.

Fingers crossed that all goes to plan.

And some “human interest” background about the Leros engine, copied from an article in The Sunday Times:

This is it, son: Jupiter mission rests on us

Jonathan Leake, Science Editor

June 26 2016, 12:01am,

The Sunday Times

The fate of Nasa’s ambitious attempt to put a probe into orbit around Jupiter depends on an engine built by a father-and-son team from Buckinghamshire.

The engine assembled by Mike and Nick Hodgins will begin a crucial 35-minute burn next week aimed at decelerating the speeding Juno probe so that it can enter orbit around the giant planet.

The stakes are high. If the engine succeeds, Juno could carry out some of the most innovative research yet done around another planet. If it fails, the £770m probe will hurtle into outer space.

Mike Hodgins, from Aylesbury, who left school at 16 and then took a City and Guilds certificate in engineering, built the engine with his son after Nasa commissioned Moog Westcott, their employer, to provide Juno’s propulsion.

“I started out as an apprentice engineer in 1970, but I have been building these rocket engines since the late 1980s,” said Hodgins, 62. “I bolt or weld them together and then test them — it takes about a month to assemble each one. Then they get shipped away for fitting to the spacecraft.”

Hodgins and his son, 28, who joined the firm after taking an engineering degree, built Juno’s engine some years ago — Juno was launched in 2011 but is only now about to arrive at Jupiter.

Its crucial moment is due at about 4.15am on July 5, British time, when Nasa’s software will release two volatile chemicals into its combustion chamber, where they should spontaneously ignite.

For an engine measuring 3ft long and weighing just 9lb, the energy the reaction will release is intense — roughly equivalent to the output of a Formula One racing car. The engine’s temperature will rise from near absolute zero to around 2,800C as it burns 300 litres of propellant in 35 minutes, squirting hot gases into space at 7,000mph.

“Juno is currently overtaking Jupiter on its track around the sun, travelling 1,118mph faster than the planet,” said Ian Coxhill, chief engineer at Moog Westcott, who oversaw the engine’s design. “The engine’s job is to decelerate Juno so that its speed matches that of Jupiter.”

Nick Hodgins described the Juno mission as the “cutting edge of space science” and said July 4 and 5 would see “a lot of bitten fingernails”.

Moog Westcott has a rich history. In the 1950s it was a UK government research centre, running the nation’s guided missiles programme from the Westcott RAF base, from which it gets its name. Nowadays the engines built by Hodgins and his colleagues are used mainly for communications satellites — but an interplanetary mission is something special.

Jupiter has fascinated astronomers since Galileo turned his telescope on it in 1610, but little is known about anything under its thick gas clouds.

Juno’s task is to peer through those clouds. One instrument will measure the gravity to see if there is a rocky planet like Earth hidden within.

Another will study Jupiter’s atmosphere, hunting for hydrogen, which may exist as a metallic liquid that conducts electricity, generating the planet’s magnetic fields.

Juno has travelled 1.7bn miles but will last just two years because the planet’s radiation will wreck its instruments.

The success of the mission now depends entirely on the firing of the rocket engine. Hodgins Sr and Jr will be getting up early to watch it on Nasa’s internet channel. They will, however, have no idea if it has worked as planned until after the rocket has finished firing. This is because Jupiter and Juno are so far from Earth — now about 500m miles — that radio waves take 45 minutes to reach us.

Meanwhile, the duo have moved on to other projects and are now working on a new engine, with twice the power of the Juno version, to power a European Space Agency “sample-return” mission to bring back the first rock samples from Mars.

Mike Hodgins’s rockets have reached other ambitious destinations — he co-built the motor powering Nasa’s Near Shoemaker probe when it landed on Eros, an asteroid, in 2001.