If you’ve read some of our other blog posts, you’ll see we’re obsessed with color science. Since the relationship between CRI and luminous efficacy is frequently noticed but rarely understood, we thought this was a question/topic that definitely deserved a dedicated post.

To understand CRI and lumens, look at the spectrum

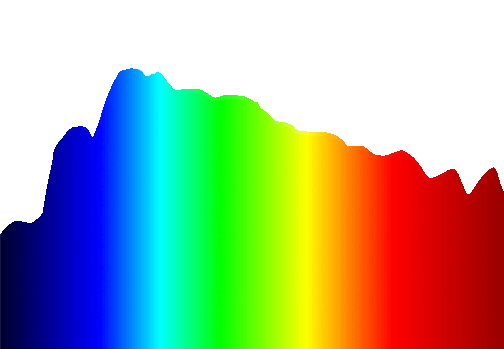

As with many things in color science, we need to go back to the spectral power distribution of a light source.

CRI is calculated by looking at a light source’s spectrum, and then simulating and comparing the spectrum that would reflect off of a set of test color samples.

CRI uses the daylight or black body SPD in its calculation, so a higher CRI also indicates that the light spectrum is similar to natural daylight (higher CCTs) or halogen/incandescent (lower CCTs).

Natural daylight spectrum (above)

Luminous output, measured in lumens, describes the brightness of a light source. Brightness , however, is a purely human construct! It is determined by what wavelengths our eyes are most sensitive to, and how much light energy is present in those wavelengths. We call ultraviolet and infrared “invisible” (i.e. no brightness) because our eyes simply do not “pick up” these wavelengths as perceived brightness, no matter how much energy is present in those wavelengths.

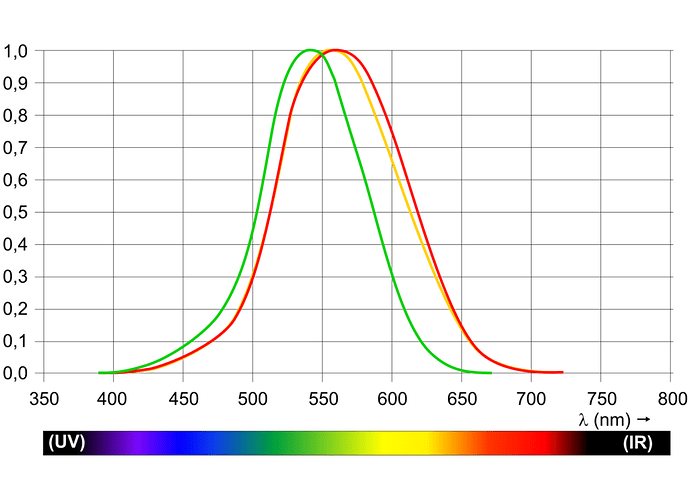

The Luminosity Function

To better understand how the phenomenon of brightness works, scientists in the early 20th century developed models of human vision systems, and the fundamental principal behind it is the luminosity function, which describes the relationship between wavelength and perception of brightness.

Yellow curve shows the standard photopic function (above)

The luminosity curve peaks between 545-555 nm, a lime-green color wavelength range, and falls off quite rapidly at higher and lower wavelengths. Critically, the luminosity values are very low past 650 nm, which represent red color wavelengths.

What this tells us is that red color wavelengths, as well as dark blue and violet color wavelengths, are very ineffective at appearing bright. Or, conversely, green and yellow wavelengths are the most effective at appearing bright. Intuitively, this can explain why high-vis safety vests and highlighters most commonly use yellow/green colors to achieve their relative brightness.

Finally, when we compare the luminosity function to the spectrum for natural daylight, it should become clear why high CRI, and especially R9 for reds, is at odds against brightness. To pursue high CRI, a fuller, wider spectrum is almost always beneficial, but to pursue higher luminous efficacy, a narrower spectrum focused in the green-yellow wavelength range will be most effective.

It is primarily for this reason that in the pursuit of energy efficiency, color quality and CRI are almost always relegated in priority. To be fair, some applications like outdoor lighting may have a stronger need for efficiency than color rendering. However, an understanding and appreciation of the physics involved can be very helpful in making an informed decision in lighting installations.

Luminous Efficacy of Radiation (LER)

So far in this article, we’ve somewhat loosely interchanged the terms efficiency and efficacy. Although they both impact the final number of lumens emitted per watt of electrical energy, technically, these terms mean different things.

In a strictly scientific sense, efficiency describes the total electrical energy consumed (input) compared to the total energy emitted as light. Since it is a ratio, both input and output are described in watts, and the output watts are typically described as “radiometric watts.” In short, radiometric output energy is the the energy in the form of electromagnetic radiation, regardless of its effect on perceived brightness. A 50% efficient LED will convert 100W of electrical energy into 50W of electromagnetic radiation, and 50W of heat energy.

Now, when we move on to efficacy , we bring the luminosity function into our discussion. Luminous efficacy describes how effective a particular light output is at creating the perception of brightness. A low CRI light with lots of green and yellow wavelength energy, by virtue of the luminsoity function, will have a higher luminous efficacy, while a high CRI light whose light spectrum is fuller and evenly distributed, will have a lower luminous efficacy, because those wavelengths are less effective at creating perceived brightness.

Deep in the R&D labs of LED development, engineers constantly evaluate this compromise between color quality and efficacy. A convenient measure called Luminous Efficacy of Radiation, or LER for short, helps to quantify this.

In essence, LER takes away the electrical efficiency aspect of LEDs from the equation, and focuses on the radiometric output and its efficacy in creating perceived brightness.

LER can range in value between 0.0 and 1.0, depending on the spectral power distribution, and can be used to estimate the actual luminous efficacy in lumens per watt using the following equation:

LPW = Fe x LER x 683

LPW: Luminous Efficacy, in lumens per watt

Fe: Radiometric efficiency (typically 30-50% for LEDs)

LER: Light Efficacy of Radiation (typically 0.2 - 0.5 for LEDs)

683: Factor to convert LER to LPW

So, as an example, if we have an LED that has a 40% radiometric efficiency, and an LER of 0.40, we can estimate that it would produce a luminous efficacy value of approximately 110 lumens per watt.

As a side note, we can also infer that a 100% electrically efficient LED with a 100% LER (one that emits only at 555 nm) can have a maximum luminous efficacy of 683 lm/W.

The takeaway? Not only can one increase luminous efficacy by increasing the inherent electrical efficiency of an LED and its system, but by also looking at the LER which can be derived directly from a light’s spectrum.

Bottom Line

So, there you have it - a comprehensive look at why higher CRI, and by extension a wider spectrum, will almost inevitably result in a lower luminous efficacy. It’s a fundamental physics problem, and requires a bit of human judgment to determine when and where to compromise on efficiency/efficacy versus color quality.