I dub thee: El Jefe.

It is the boss is because it starts out cold at 270 watts (about 34,000 raw lumens), then when it warms up, it stays at 270 watts. Indefinitely. The power level was defined by the amount of heat that could be shed operating at 100% continuous duty under worst case conditions - which would be parked, idling, on a hot desert night, so no airflow in an ambient temperature of 100°F / 37.8°C.

Commercially available light bars cannot do this, their heat sinks are much too small and they have to enter thermal management.

HIDs don’t dim, incandescents don’t dim, why can’t LEDs maintain full power indefinitely too? They can, with enormous heat sinks made from time, money and pain.

Below are before and after photos all taken at ISO 100, f8, 1 sec shutter. Afterward I raised the black level (identically across all photos) to approximate the real life visibility. Stock high beams are the reference.

Shot 1 - Standing on the roof rack to try to capture the field of view.

How sharp is the curve ahead? Spotlights don’t help with that question. A spot would be pointed off the trail 80% of the time. El Jefe’s lenses have an elliptical pattern, basically a spot vertically but a flood horizontally, 13 degrees by 46 degrees. The extremely wide field of view is a little surreal - the visible area is much wider than the windshield, and your peripheral vision is seeing things through the side windows, similar to daytime. Driving is eerie in that the lighting doesn’t move as the steering wheel is turned, it’s everywhere. It’s fantastic.

I’m going to tilt it up 1-2 degrees to put a little less light on the ground in front.

Shot 2 - Normally, having an LED light bar with a white hood is like a pig farmer wearing a white suit to work.

Over-windshield mounted light bars put so much glare on the hood that many people paint or wrap the hood matte black. Rather than do that, I mounted it back from the windshield to let the roof shield the hood - just like the old days when pickups mounted their KC lights behind the cab. Grille mounted lights are more prone to being obscured by rocks and bushes.

Shot 3 - The only light on the hood is reflected off the hill.

Shot 4 - A spotlight would show where the trail isn’t. The wide beam makes it much easier to find landmarks and turnoffs. This light was designed for following twisty desert trails at 30 mph on Friday night looking for the camp site because I’m already late.

Shot 5 - Entrance to Wall Street Canyon. Just because it looks cool.

In order to maintain power continuously without dimming, I had to come up with an unusual heat sink design.

Most manufacturers use the same heat sink design, with minor variations, and that plays a bigger role in the light output than the advertised power. For example, if a given physical size can dissipate 115 watts, it won’t matter if one light bar is 200 watts and another 400 watts - they will both settle to 115 watts after they warm up and thermal management kicks in.

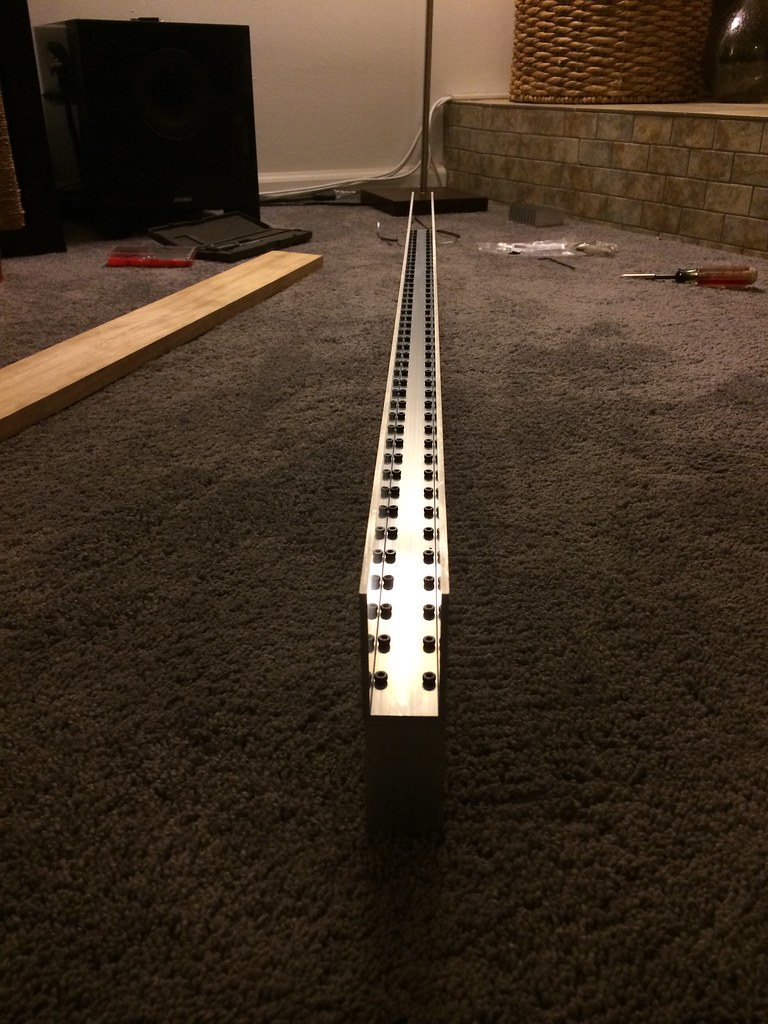

Typical horizontal heat sink fins simplify manufacturing, but most of the surface area is wasted since fresh air can’t really get in between the fins and just skims the tips. Bolting a couple of CPU fans on the back of a light bar to force air between the fins wouldn’t be difficult (I actually searched for waterproof fans), but probably not durable. Instead I opted for slicing the heat sink up like a loaf of bread and mounting the fins vertically. It was a ridiculous amount of work, but the short vertical fins are exposed to fresh air across their entire length without any stagnant pockets.

I learned the hard way, spending many hours building prototypes, starting with the cheapest heat sink in the foreground and reluctantly working up to the biggest to sustain El Jefe’s 270 watts. I wanted a low-profile light and I hated the way the big heat sink looked, but I’ve warmed up to it. Getting the most lumens out of those watts comes after.

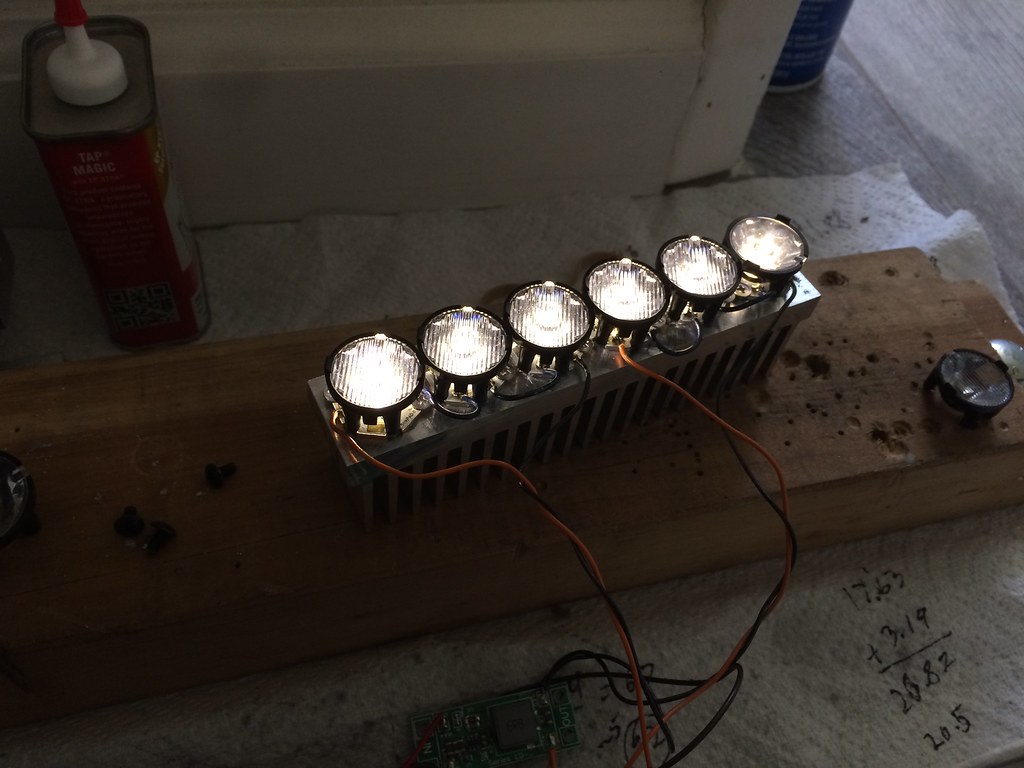

Early prototype with short heat sink and Carclo elliptical lenses. TIR lenses focus more of the lumens and lose less as spill than typical reflectors. Spill on a vehicle mounted light mostly glares off the hood, saturates the ground 4 feet in front of the car, or goes off into space.

Three LED prototype of the final design undergoing heat torture test. The meat thermometer was surprisingly effective. The temperature was recorded in 30 second intervals for half an hour, when it stopped rising, then the results of all the tests were graphed and compared. For consistency, there needed to be absolutely no airflow across the fins other than natural convection. I noticed that just moving my hand past the sink too quickly would cause the temperature to dip.

In this test with 6 watts per inch of width the temperature leveled out at 137F in 70F ambient. Painting the fins black produced virtually identical results so didn’t have an insulating effect. Projecting these numbers to 100F ambient, it should peak at 167F. With the thermal losses between the LED, circuit board, frame and heat sink the LED chip should be very close to the binning temperature of 85C (185F). No thermal management dimming needed. I just need to take care not to leave the light on, parked, with no wind in 105F weather.

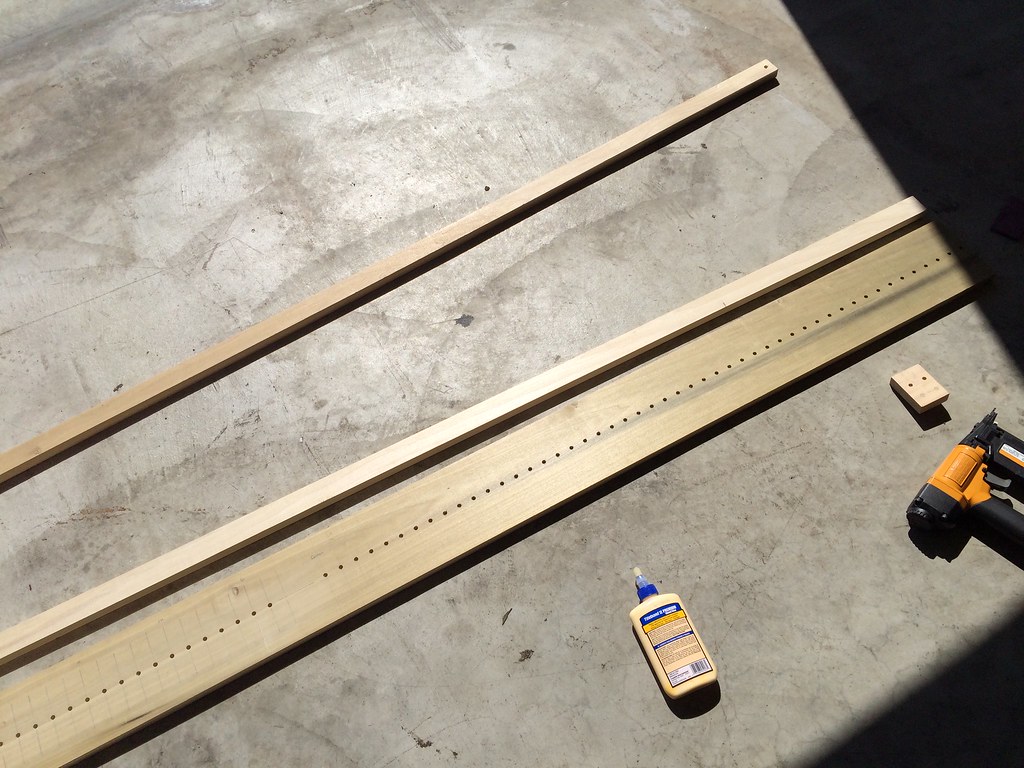

Done designing, starting the build. I made a jig to drill the holes consistently on the drill press. The stops increment at 25mm, with different spacers for different offsets. In case I make another…

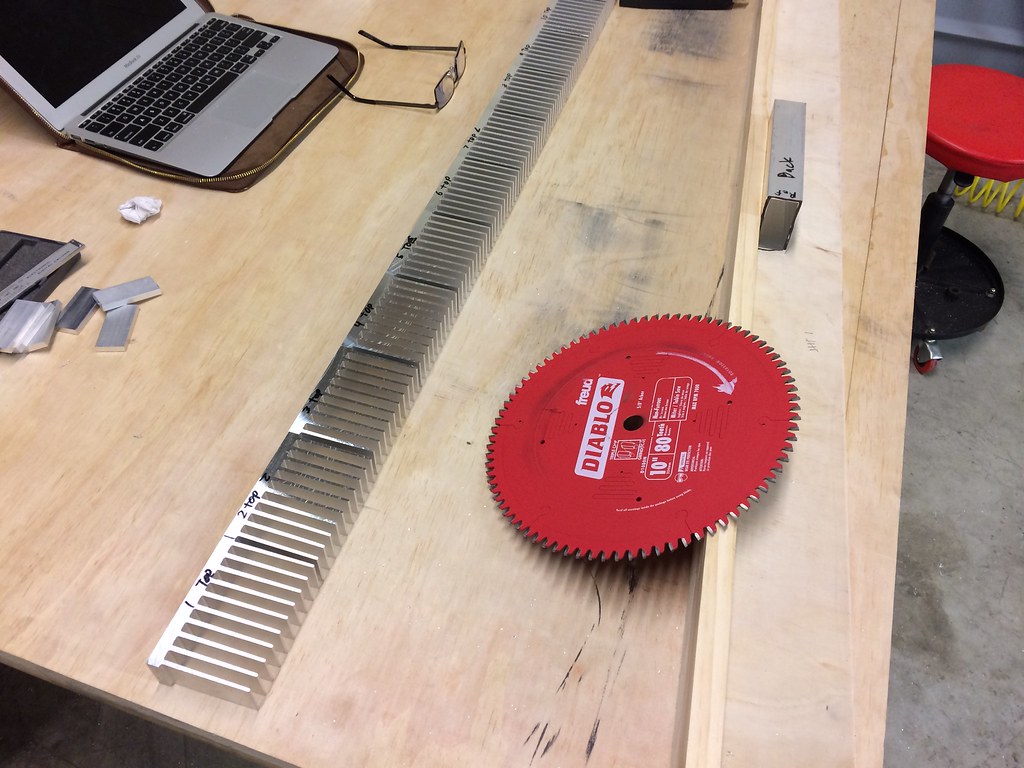

Creating the frame by turning a rectangular tube into a channel with a table saw. The non-ferrous blade in the table saw made a clean cut but it was risky. A band saw with file cleanup would have been safer.

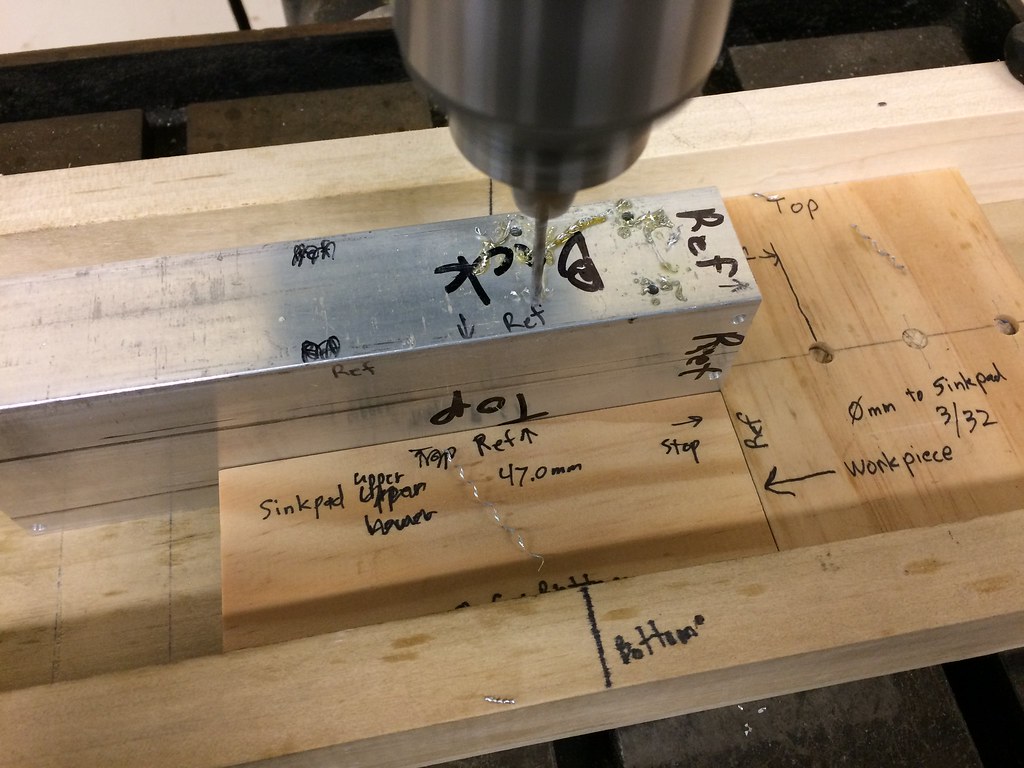

Rather than reposition the jig for each row of holes, I used a system of wood blocks as spacers for the various mounting holes so I could leave the jig locked down and offset the frame from the sides by the same amount every time. Measuring one hole at a time would have been miserable and error-prone.

From http://www.heatsinkusa.com/ That pile of shavings is from hand-filing the mounting surface absolutely flat for maximum heat transfer. Took three hours. Great for the triceps.

Moved the blade to the miter saw and cut the heat sink into slices. I didn’t think to account for blade thickness and losing over an inch of material just for the cuts so I ran short and had to order another chunk of extrusion.

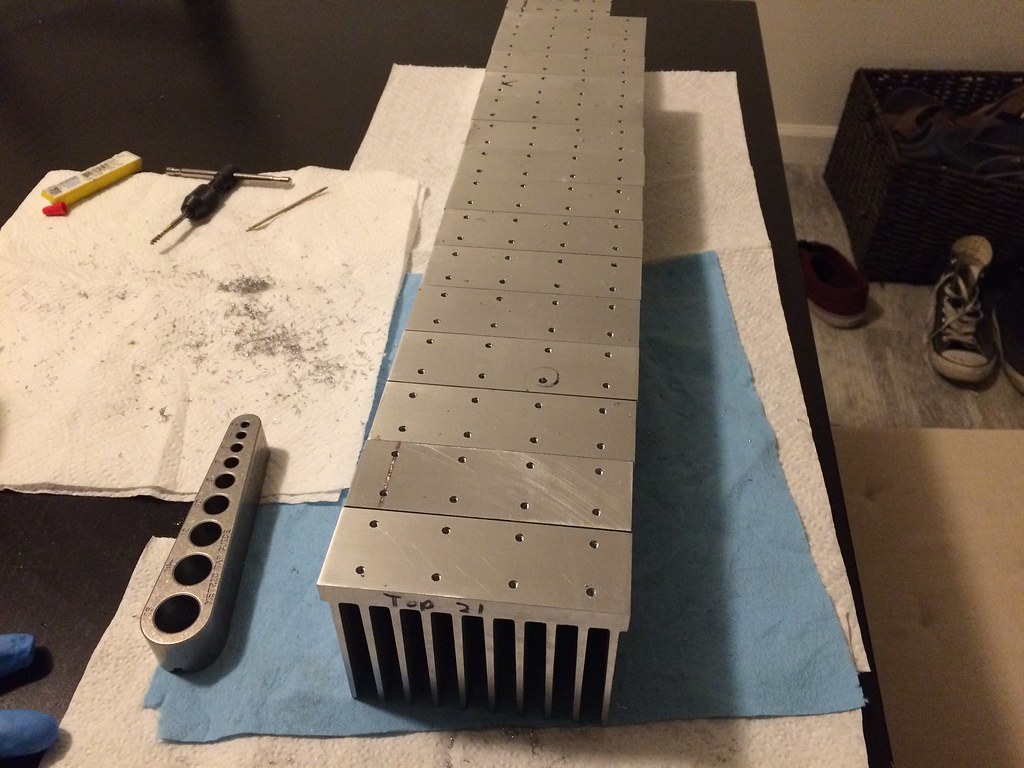

Drilled and tapped for M3. That tapping guide is the most clever invention ever. I broke two taps going in crooked before, none after I started using it. http://www.shop.biggatortools.com/product.sc?productId=5&categoryId=4 The tap is from MSC Direct and it cut 10 times better than the consumer taps. Buying professional drill bits and taps turned out to be well worth the cost.

Test fit. The saw marks on the fins were unacceptable.

The accuracy and finish from the miter saw was pretty good but not good enough so I fly cut to final dimension and finish. This added another week and a half to the project. I didn’t know what a fly cutter was until I needed one, then I had to learn how to make it and learn how to use it. I’m an electronic engineer and I thought I was starting an electronic project but 90% of the time and difficulty was in machining.

One set of M3 screws clamp the heat sinks to the frame to the star boards like a big sandwich. That saved another 180 holes drilled and 90 tapped over using separate screws.

Using the light bar frame as guide to drill the faceplate (.220” thick acrylic). I’ve noticed light bars on other cars starting to yellow with age, just like old headlights, so instead of using polycarbonate like everyone else, I used acrylic, which does not turn yellow in the sun. Polycarbonate is stronger than acrylic, but even acrylic is 16x stronger than glass and I don’t think the yellowing is worth it.

180 holes drilled for LED and heat sink mounting, 75 for current drivers, 24 for end plates, 3 for the power cable, 88 for the faceplate, 4 for the mounts, 1 for a Gore vent.

375 holes drilled, 228 hand-tapped.

Cleaned of all shavings and cutting oil and ready for primer.

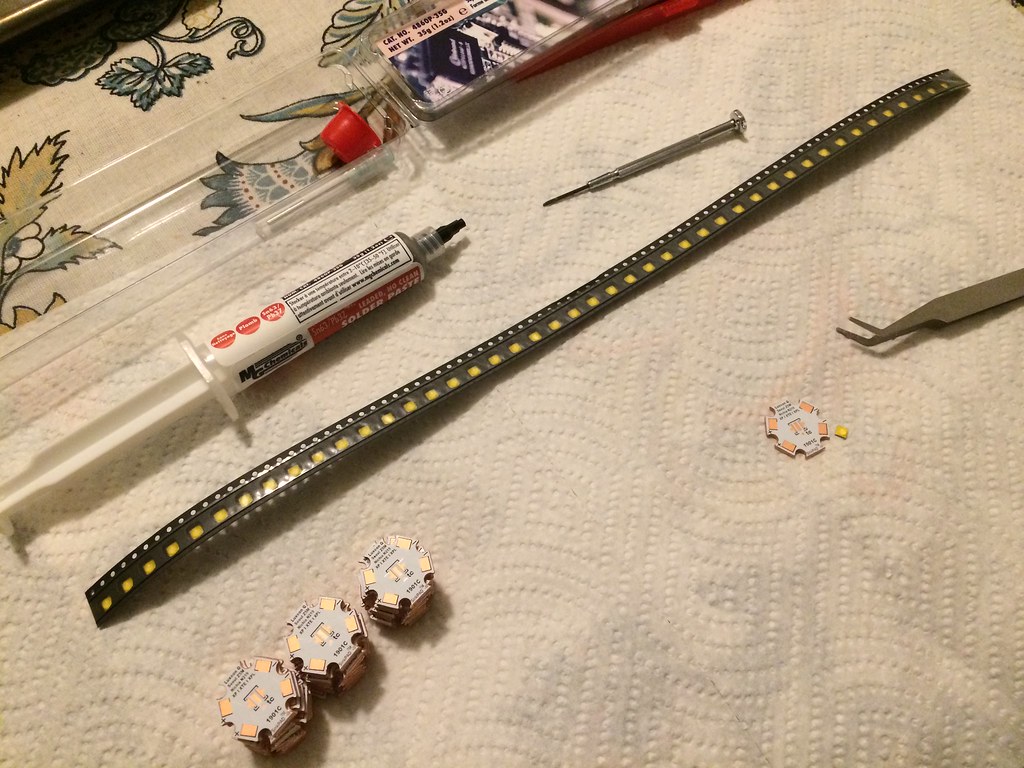

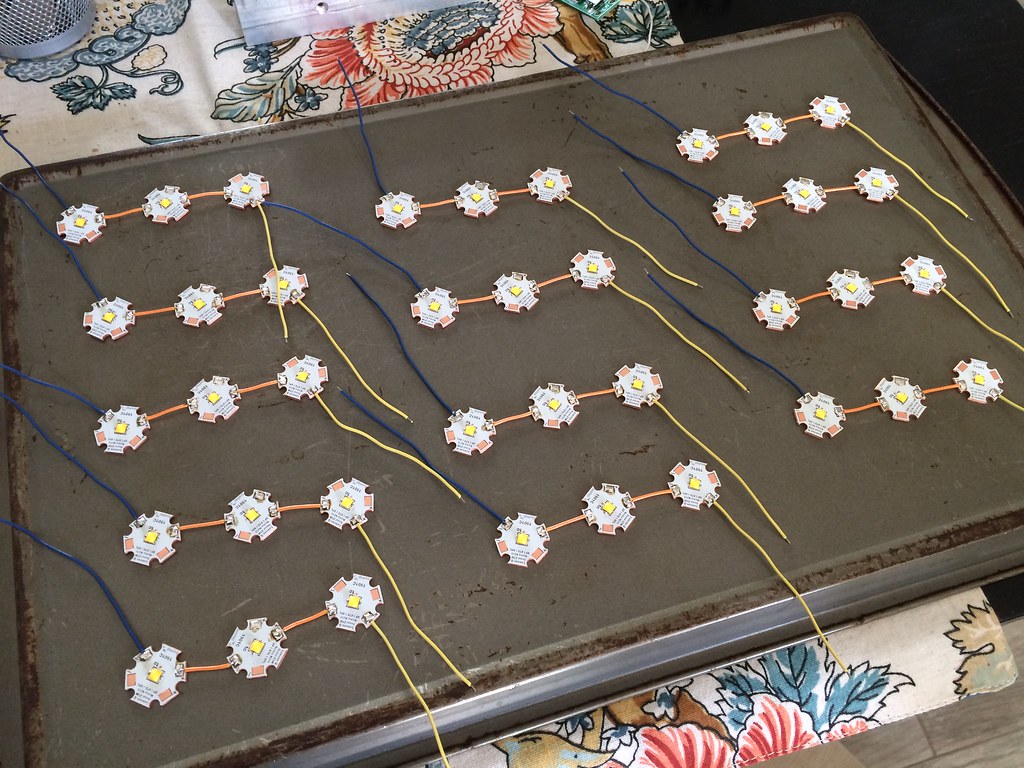

Cree XP-G3 70 CRI minimum. 4000k for a neutral white. 777 raw lumens each driven at 2 amps (6 watts). Reflow soldered to SinkPad MCPCBs on the electric stove.

45 LEDs in gangs of 3. Soldering the wires onto the star boards was like trying to boil water with a lighter. The copper MCPCBs are amazing at pulling away heat.

Russian LED current drivers from eBay. Configured for 2A. There are lots and lots of current drivers on eBay but I liked these for compactness and no frills - no strobe or SOS modes etc. El Jefe has only one mode: ON.

The 14 ga power cord continues inside to become the power buss, with taps for each driver. Space is so tight I used the chassis for ground to eliminate one wire. Even so, that 14 ga white wire barely fit. Lens mounts are epoxied to the star boards.

15 current drivers, blue tape to hold them in place while soldering.

In order to get the lowest profile possible, I let the current drivers obstruct some light. I aligned the inductors to block the least possible.

The design is for function, not for looks. The frame has an extra 12mm in front of the faceplate to block most of the spill from going into the sunroof. The amount of spill is small as a percentage, but even a small percentage of 35,000 lumens is a lot of light. I had an ebay light bar which looked cool but didn’t light up anything but the dashboard. People keep asking me why I took the light bar off my car, because El Jefe blends into the roof rack and they don’t see it. Deutsch connector mates to a Rigid wiring harness.

Mounts cut from discarded HP server mounting rails and gas-welded to cheap roof rack. Building a custom roof rack is the next project.

Not bright at all off-axis and it adds no wind noise.

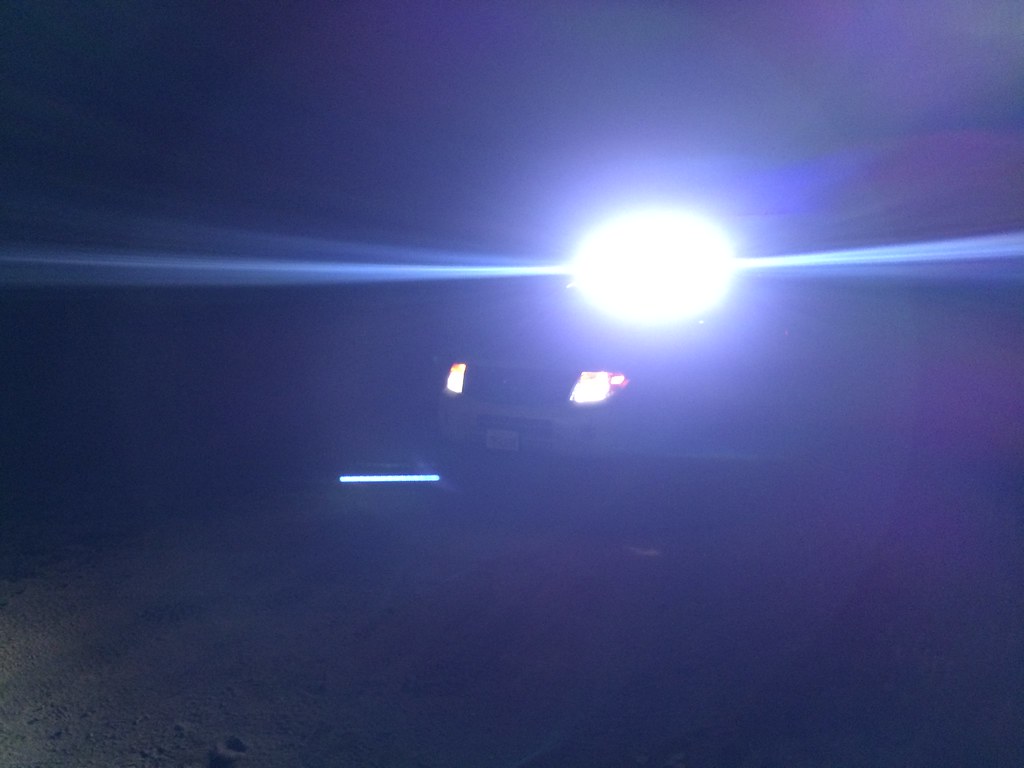

It’s physically painful to look at even in noon sun.

Pretty lens flare.